BRANDS CONNECT WITH DIGITAL NATIVES

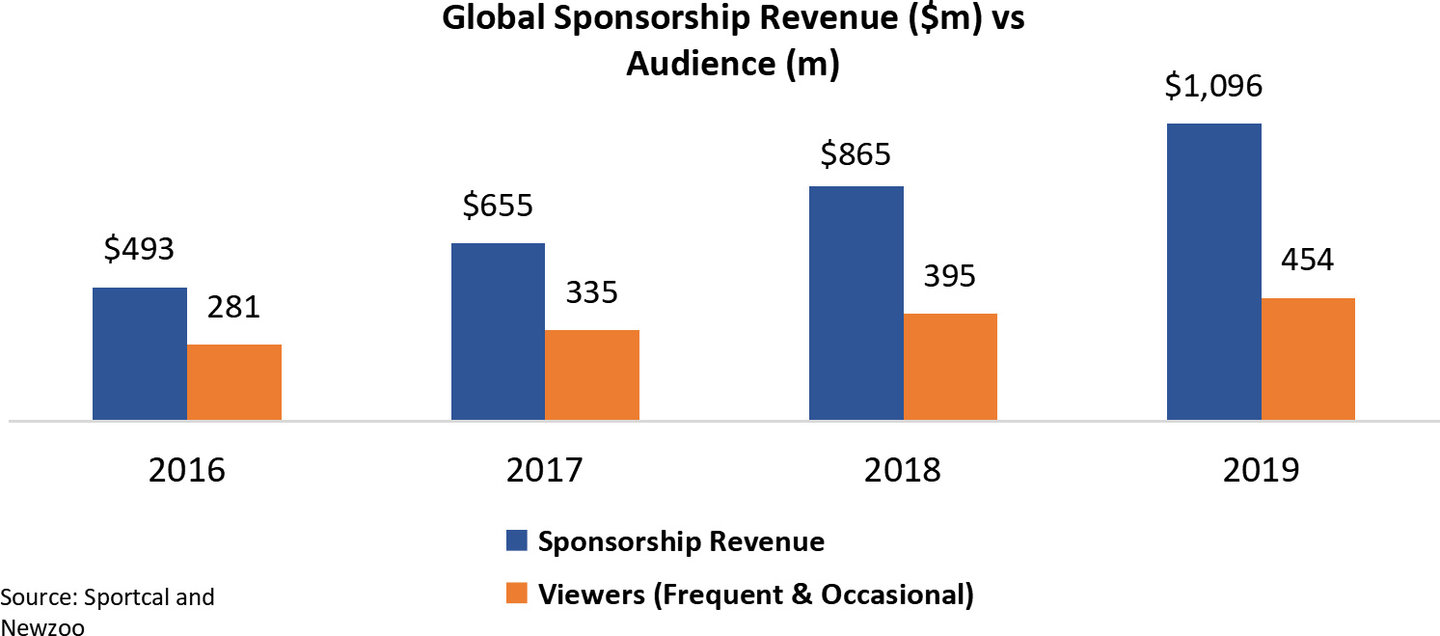

Last year was a symbolic one for the burgeoning esports industry, with total revenues calculated to have surpassed $1 billion for the first time, driven in large part by growth in sponsorship as companies from multiple sectors sought to gain or deepen an association with the discipline.

Brands now active in the space range from Turkish domestic appliance brand Beko to French luxury retail company Louis Vuitton to US telecoms giant Verizon.

Of the estimated $1.1 billion in global esports turnover in 2019, brand investment accounted for $646 million, of which sponsorship made up $457 million and advertising $189 million, according to market intelligence provider Newzoo.

The company forecasts that the brand figure will climb by a further 23 per cent to $795 million in 2020, including $584 million in sponsorship (up 28 per cent), accounting for nearly three-quarters of the total, and $211 million in advertising (up 12 per cent).

Sponsors have been attracted by a global audience (those watching some form of esports content) that hit 454 million in 2019, up 62 per cent from 281 million in 2016, but more particularly the often hard-to-reach 18-to-35-year-old demographic.

Much of the content is consumed on digital platforms such as YouTube and Twitch, the Amazon-owned video streaming platform, and under-35s accounted for 79 per cent of total viewership in 2018, according to Goldman Sachs.

THE PUBLISHER – RIOT GAMES

The brands that initially allied themselves with esports were primarily endemic, namely from the equipment genre, but the sector has subsequently attracted FMCGs and sportswear firms, and increasingly high-end brands such as cars and luxury goods.

Alban Dechelotte, head of sponsorship and business development EU Esport at leading video games publisher Riot Games, tells Sportcal Insight: “Ten years ago we had brands coming on stage that were the performance brands, the equivalent of Adidas and Nike in football. We had computers, screens, keyboards, mice and headsets as they talked to the players – if a pro uses us, you should use us if you want to perform.

“Then we had the second generation that probably started with Coke. I was very close to that. It was the first time brands like that started to go in, to talk to the audience. They identified that, beyond performance, there are consumers, and if they created a meaningful connection with this ecosystem, they could engage with the audience in a powerful way.”

Riot Games, owned by Chinese internet giant Tencent, is the developer behind the popular League of Legends title and competitions.

Dechelotte, a former executive at Coca-Cola and Havas, the French advertising agency, detects a sea change with companies like Beko and Louis Vuitton branching out in becoming sponsors of the LoL European and World Championships, respectively, in the past year.

“They [brands] want to build a collaboration with us to tell a story to the world.”

“We are entering the third generation now. They [brands] want to build a collaboration with us to tell a story to the world,” he says. “I’m going to use Beko [as an example]. They have a commitment that is ‘eat like a pro if you want to play like a pro’, and they use us and FC Barcelona and Fenerbahce, the leading basketball club, to tell the story.

“It’s a model in which they don’t just talk to League of Legends fans, they talk to the world, and the same thing for Louis Vuitton. Louis Vuitton is not only targeting players of League of Legends, but I think it [esports] is also something that builds equity for brands because it’s a message that you are open to the world of the digital native.

“It’s the sport of the digital native. We play online, we work online, we talk online. That is how the sport is played and shared, and I think brands associating their DNA and heritage, and celebrating this youth, is powerful not only for a transactional relationship with the existing community of League of Legends fans, but to talk to the world.”

The LoL European Championship (LEC) evolved from the World Championship, taking on its current name in 2019, and the esteem in which it is held is shown by the fact that prominent agency Lagardère Sports signed a multi-year deal to act as its exclusive sponsorship agency, and partners include familiar brands such as Kia, Shell, Red Bull and Pringles.

Sponsorship accounts for 80 per cent of LEC commercial revenue, far outstripping broadcasting on 15 per cent and gameday on 5 per cent.

THE LEAGUE – NBA 2K

Sponsors familiar with sport have tended to gravitate towards simulations when entering the esports field, with video games series such as FIFA more closely aligned with their area of knowledge than the violent non-sports titles.

Competitions such as the NBA 2K League, backed by the top basketball league and game developer Take-Two Interactive Software, have attracted a mixture of endemic and non-endemic brands, including AT&T and Bud Light.

Brendan Donohue, the managing director of the league, says: “There’s definitely NBA partners, and we have relationships with them, which is great, but a majority of our partners have been new to the NBA, like Snickers and [sportswear brand] Champion.

“We’ve been really selective in finding partners who are going to help us grow the league. Having Champion, for example. They had their 100th anniversary in 2019, and their global marketing campaign included the 2K League, which was amazing for us in terms of awareness of what we’re doing.”

The NBA 2K League involves teams representing the actual franchises, and is expanding to 23 outfits for its third season in 2020, including a first international entrant in China’s Gen.G Tigers of Shanghai.

Asked why the league appeals to sponsors, Donohue responds: “I do think they know they can trust the NBA and NBA 2K with their brand, and that we’re going to activate in a responsible way, as we’ve been activating partnerships for 75 years. I also think that we get some feedback about their comfort level and putting their brand next to ours.

“Our game is rated E for everyone so from a gaming perspective, it’s a safe place to put their brand. The last thing I’d say they like about us is they can easily integrate into the digital experience.

“When you watch our games, we have courtside signage and brands on the court, it’s a normal NBA experience. That enables us to bring the brands into the digital part of the game, which is not that easy in the rest of esports.”

THE TEAM – DIGNITAS

In the same way that brands have embraced sports simulations, so sports organisations have taken to esports, including the more endemic games.

Dignitas, the US esports team, was acquired by the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers in 2016, and now forms part of Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment, the holding company that oversees the various franchises and properties of US financiers Josh Harris and David Blitzer.

Dignitas, which is based in New Jersey, recently secured a major sponsorship deal with telecoms giant Verizon, which will pave the way for a new 5G training facility at the latter’s headquarters in Los Angeles, making it the first North American team to have a dedicated presence on both coasts.

It is Verizon’s first serious venture into esports, and the company will make available its 5G Ultra Wideband network, ensuring fast connectivity and low latency that is intended to aid player performance and engagement with fans among various benefits.

“The non-endemics are coming into the space in a clip, and we’re seeing the smarter non-endemics like Verizon and Louis Vuitton.”

Michael Prindiville, the chief executive of New Meta Entertainment, the new parent firm of Dignitas, describes the latest sponsorship deal as “the most exciting partnership we’ve seen in the space” because of the technologies it comes with, and a “match made in heaven.”

He recognises the trends in the esports sponsorship market, saying: “The non-endemics are coming into the space in a clip, and we’re seeing the smarter non-endemics like Verizon and Louis Vuitton. You might say, ‘why is a brand like that [Louis Vuitton] getting involved?’ But not when you see how engaged and authentic it is, and the online and digital opportunities there are.”

Under its sponsorship of the LoL World Championship, Louis Vuitton has designed a trophy travel case to hold the Summoner’s Cup, which is awarded to the champions, and outfits for playable characters within the game.

Dignitas, which last year merged with another esports team Clutch Gaming, competes in games including LoL, Rocket League and Counter Strike: Global Offensive, and Prindiville claims that these are ultimately the best platforms for attracting sponsors.

“When a non-endemic brand is looking to enter the space, there’s an education, and that can start with a sports simulation,” he says. “These games have large audiences, but when you dig into the data, they are underdeveloped, and your true scale comes from the endemic esports games like League of Legends and CS:GO. If you want that 18-to-34 demographic then the games with scale are the endemic ones.”

HBS&E’s level of commitment is demonstrated by the fact that it led the $30-million funding round for Dignitas that concluded last September, and coincided with the launch of NME, a company that oversees three verticals in esports teams, content and marketing, and investments.

There is also a distinctive element in Dig Fe, the two-time world champion female CS:GO team, which can attract different types of sponsors to the esports table.

Heather Garozzo, vice-president of marketing at Dignitas and herself a former top player, says: “There are lots of opportunities for female-focused brands who appreciate these women are big influencers on social media and live streaming.”

Esports: a legal lens on a billion-dollar industry

By JJ Shaw

Everybody wants a piece of the esports pie, with even ‘traditional’ sports entities muscling in on the action. In September 2019, the International Cycling Union (ICU) teamed up with the virtual cycling app Zwift to announce the world’s very first ‘cycling esports world championships’ to be held in 2020; between December and April, the Madden NFL 20 Championship Series takes place with a prize pool of $1.3m; and, in March 2020, the ePremier League (ePL) returns for its second season to be broadcast on Sky Sports.

Emerging legal and regulatory issues

As the industry expands, however (revenues are expected to have topped $1.1 billion in 2019), and more ‘players’ seek to enter the market, a variety of structural, legal and regulatory issues are emerging, and which the esports industry must successfully navigate in order to fully realise its commercial potential over the longer term.

Lack of overall regulation

Esports is currently a multi-million-dollar industry without an official governing body or any coherent regulatory framework. Perhaps the closest thing esports has to an integrity body today is the Esports Integrity Coalition (ESIC), formed in association with major esports organisations such as Electronic Sports League (ESL), ICSS (International Centre for Sport Security) and SIGA (Sport Integrity Global Alliance).There has been speculation regarding whether esports will eventually make its way into the Olympic programme, but the challenge of regulation may hamper progress in this regard. Ahead of the 2020 games, the Olympic Summit discussed esports at its December 2019 meeting in Lausanne and encouraged international federations to consider implementing stronger esports governance. All eyes will be on the Esports Regulatory Congress in September 2020 as esports leaders seek to overcome this hurdle.

Doping and Integrity

The ESIC’s mission statement is: “to be the recognised guardian of the sporting integrity of esports and to take responsibility for disruption, prevention, investigation and prosecution of all forms of cheating, including, but not limited to, match manipulation and doping”.

However, the risk of doping in esports is very much alive, with some pro gamers having admitted to taking concentration drugs such as Adderall during major competitions. ESL, one of the world’s largest and longest running esports tournament organisers, has successfully devised and implemented an anti-drug policy for esports, working in conjunction with the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). The policy involves random drugs tests for gamers, much in the same way that conventional athletes in traditional sports are subjected to. This policy has not yet been adopted by all tournament organisers, however.

Elsewhere, the UK Gambling Commission has already published a discussion paper outlining the need to impose strict gambling regulations on esports at all levels, also highlighting the risks of using ‘cryptocurrencies’ to place bets on competitions.

Esports player contracts

There is still no industry standard for precisely what an esports player contract should look like. Esports athletes tend to be young and inexperienced, often entering the scene at the age of 15 or 16. Tournament prize money in esports is increasing at an average rate of 42 per cent a year and will top $173million in 2019. Without precedent, negotiations risk clear inequality of bargaining power between these young players and more sophisticated esports organisations as well as a lack of enforceability. Questions remain as to whether esports players require intermediaries to ensure fair representation, whether esports athletes ought to enjoy contractor or employee status, and whether contracts should include provisions for visas and travel. These questions are all significant when it comes to legal issues such as control of player business and sponsorship activities, income and employment tax, workers’ compensation, working hours, unionisation and confronting unfair labour practices.

Intellectual property

Unlike traditional sports, where the sport itself is not a protected IP asset, in esports the video game’s publisher or developer owns the IP rights (including copyrights, trademarks, licensing arrangements and patents) to the underlying game. These rights are then licensed to the likes of broadcasters, platforms and leagues for a fee. Currently, many game publishers have no agreement with tournament organisers, while third parties (esports athletes and clubs) make money from rights they do not actually own. To remedy this, complex licensing agreements are needed to balance the often-competing interests of the publisher/developer (seeking to maximise licensing fees and retain a certain amount of control over their IP) and the relevant licensee. Rights to player names (real and in-game) and the avatars they create is also a matter that needs to be addressed in T&Cs for games and events. In traditional sports, players have influenced contractual terms relating to use of players’ name and image rights through collective bargaining and this trend may be followed in esports.

Where does this leave us?

It is no wonder given the esports industry’s explosion into the mainstream, that governance and law is playing catch up. On the one hand, this provides something of a blank slate for those looking to get into the industry, resulting in huge opportunities for gaming business and traditional sports teams and enterprises who see real value in esports as complementary to their existing operations. On the other hand, some have called the industry a ‘Wild West’ – as so many nascent and disruptive forces are posing potential risks for those looking to get into the industry without professional advice. The challenge now will be for the esports industry to mature in such a way that it attracts the investment and recognition that it is seeking, while not curtailing the ‘free spirited’ and largely flat structure which has given esports such life and vitality to date.

JJ Shaw is an associate in the sports business team at the law firm Lewis Silkin.